Pupillage: An Inherently Unequal Path

South Africa’s legal system continues to be plagued by two major issues, those being the underrepresentation of women and Black people in the legal profession and the lack of access to legal services for the general public, especially as it relates to the access to and affordability of civil legal services. A large contributor to the second problem is the high cost of legal services, which stems largely from the low ratio of legal practitioners that SA has compared to its citizens

According to statistics from the Law Society of South Africa, as of 2022 there were currently 29 981 practising attorneys in South Africa and in 2018 the last time data was collected for advocates, there were around 3083 advocates in South Africa. It is currently estimated that as of 2023, South Africa has approximately 3301 – 3600 advocates, all of whom are meant to serve approximately 60 million people in South Africa.

Practically this ratio means that there is approximately one advocate per 15 000 individuals in South Africa.

This situation naturally leads to legal services being unaffordable for most people in South Africa, especially with regards to civil legal services. A large majority of South African’s, including the broad middle class of society, cannot afford the legal fees which practising legal practitioners charge. One of the easiest and most sustainable solutions to ensuring that the current situation is resolved in a manner that will address the above issues is to introduce more legal practitioners, especially women and Black people, into the profession by removing obstacles and impediments currently in place that cause and perpetuate the current socio-economic inequality.

“who becomes an advocate in South Africa is primarily determined by whether the person seeking to do so has the financial resources to even be considered”

Systemic exclusion

The traditional route to becoming an advocate in South Africa, which is the main focus of this article, has inherent built in features that inevitably lead to the situation described above. I argue in this paper that who becomes an advocate in South Africa, as per the manner that the route is currently structured, is not determined based on a meritocratic determination of competency in order to protect the public and integrity of the profession, nor is it based on hiring the most qualified person who is able to do the work. Rather, who becomes an advocate in South Africa is primarily determined by whether the person seeking to do so has the financial resources to even be considered to join the profession. For primarily this reason, alongside many others, it is long overdue that we as a country should confront the impediments and inherent inequality in the traditional route that candidate legal practitioners must take in order to become an advocate in South Africa.

The primary route to becoming an advocate requires a person with an appropriate legal degree, to serve under a practical vocational training (PVT) contract for 12 months, complete 400 hours course work before or during the 12 months PVT, and to pass the prescribed examinations.

The process of training under the PVT contract is known as pupillage whilst a candidate legal practitioner intending to practise as an advocate is called a pupil. Pupillage is mainly offered by the various groups of voluntary independent advocates known as Bar associations such as the Johannesburg Society of Advocates. Prospective pupils must therefore apply to one of a few Bars in South Africa for selection for pupillage.

Since there is a limited number of pupils that may be accepted and a high demand for pupillage by candidates, the individual Bars then decide which pupils to accept based on their own internal requirements. This is a rigorous process which typically involves serious scrutiny of a large number of applications, followed by an interview of the shortlisted candidates before a panel of selectors. The pupils during their pupillage will be legally eligible to obtain the right of appearance at the High Court, Supreme Court of Appeal and even the Constitutional Court, and are thus expected to be of a high standard. The Bars therefore seek prospective pupils that are among other things well-qualified, able to acquire and practice a wide range of different skills and able to complete fairly high volumes of work in a relatively short period of time.

Working for no pay

Due to the Legal Practice Council’s (LPC) pecuniary interest rule (PI rule) however, the main antagonist of this article, most prospective pupils are not able to even apply for pupillage. This is because the PI rule states that for the 12-month period of pupillage, unless prior written consent is given by the LPC, pupils are not entitled to any payment or stipend nor are they allowed to be employed elsewhere or earn any other form of income. Put simply, this rule states that during the entire training period pupils will not be paid for their work at the Bars nor are they allowed to earn any income from elsewhere during this time. This rule is the core mechanism for the exclusionary nature of the entire pupillage process.

In understanding the exclusionary nature of the PI rule, it is it helpful to divide it into its main two effects and components. The first being that according to the rule pupils are not entitled to a stipend or any payment during pupillage for their work as a pupil. The second being that pupils cannot hold any form of employment wherein they would receive any renumeration during the pupillage period unless you’ve received prior approval from the LPC through an exemption.

Unfair & unequal treatment

It is important to note that candidate attorneys earn a stipend whilst they serve their articles of clerkship and are not excluded from doing so in any manner. There exists a similar PI rule for candidate attorneys however it explicitly provides for candidate attorneys to receive renumeration. In fact, the mere suggestion that candidate attorneys should not be paid would be rightly met with furore and objections amongst the entire legal profession. The reason for the different treatment of the two professions appears to be a legacy of the previous manner in which the profession was regulated, and its continuation is not explained in the legislation or sufficiently explained elsewhere by the LPC. This treatment is especially strange given that it is widely accepted that pupillage requires a much higher level of expertise and skill than articles of clerkship, as evidenced by the fact that pupils can appear in superior courts that candidate attorneys cannot. This differentiation means those with the talent, ambition, and potential to succeed in the advocates’ profession are denied access due to finances leading to a lack of diversity in the legal profession. This, in turn results in the legal system failing to cater to the needs and interests of a broad range of South African citizens.

Practically speaking, the PI rule means that pupillage is available only to persons who in addition to having the requisite qualifications and experience, can financially support themselves for an entire year without receiving any salary or financial income from any other employment, whether on a full-time or part-time basis. The pupils must do all this whilst also attending at the Bar and maintaining all their personal expenses. It is conservatively estimated that a pupil will be required to have saved at least R250 000 – R350 000 in order to survive for a year during pupillage without a salary, however, this amount could be higher in urban areas such as Cape Town and Johannesburg. The pool of candidates, that are able to apply for pupillage is therefore a relatively small number of people, especially in a country with economic conditions such as South Africa.

Further, although pupillage is set out as a year-long programme, the financial burden on newly admitted advocates usually extends far beyond the initial 12 months, and pupils are often told to budget for a period of anywhere between 15 to 18 months as an indication of when to start expecting a reliable steady income. This is because once pupillage is completed, newly admitted advocates known as baby juniors still face a financial burden in that they must then secure their chambers from which they practice, furnish and equip their rooms, pay group fees and personal expenses, commence their practices, obtain briefs and, thereafter, await payment from attorneys which usually takes between 60 to 90 days from the month of their first invoice.

“The key result of the PI rule is the exclusion of those without the financial resources from entering the profession”

How this affects young legal professionals

Imagine a 30-year-old black woman named Ntombi, who is a law graduate from a low-income background, and has been practising as an attorney for five years. Ntombi would like to apply for pupillage to become an advocate. However, due to the non-payment of pupils, she cannot afford to work for free during the pupillage process and would not be able to sustain herself financially during this time. Her interest therefore however in becoming an advocate and her ability to do so are both rendered moot unless because she lacks the financial resources to even get in the door of the profession. This lack of access to pupillage limits her opportunities for advancement in the legal profession and perpetuates systemic gender and race-based discrimination.

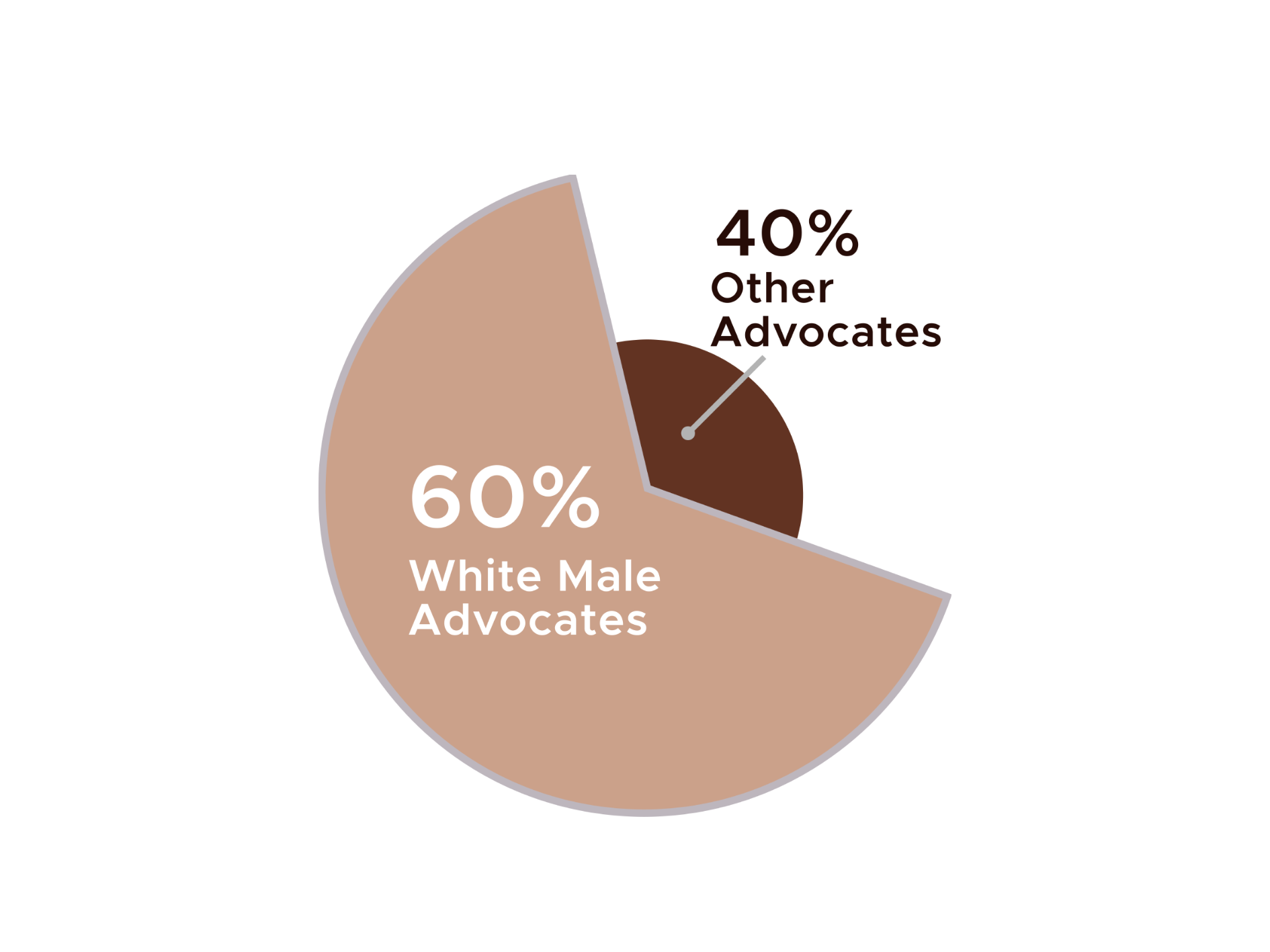

The key result of the PI rule is the exclusion of those without the financial resources from entering the profession. This then has the consequence natural result of keeping the profession limited to those with the financial resources to enter pupillage and thereby entrenching the profession of the advocate for the privileged few with money which in South Africa remains a racial and gendered class that continues to be statistically dominated predominantly by white males. The historical and present-day intersections of class with race and gender in South Africa mean that the financial exclusion of the PI rule has obvious racial and gender implications resulting in the underrepresentation of women and Black people in the legal profession.

The statistics in the South Africa legal profession especially amongst the higher ranks such as senior advocates or silks reflect the grim reality of an untransformed profession which does not represent the gender, racial and ethnic diversity of South Africa, with white practitioners still making up approximately 59% of advocates despite being less than 10% of the population.

It is therefore clear that the LPC’s PI rule deliberately perpetuates systemic discrimination and reinforces pre-existing social hierarchies whilst excluding marginalized communities from accessing opportunities for advancement in the legal profession.

An amendment to the LPC rules to overhaul the current pupillage system and amend if not remove the PI rule is a necessary direct response and a major step towards the necessary solution(s) to the two main challenges earlier identified with the SA legal system. Those being the need to make the legal profession representative of the diversity of South African society and the need to make the legal profession more accessible and affordable for the public.

This article is the first in a trio of articles addressing the above issues. The second article will cover the rationale given by the LPC and lawmakers for the PI rule and various counterarguments that exist in response to such rationale.

well done